The Silent Metal Song: A Dhokra Legacy

In the heart of India’s tribal belt, where the forest rustles with ancestral whispers and the soil remembers every footstep, there lived a community whose lives danced to the rhythm of fire, wax, and brass. They weren’t just craftsmen—they were storytellers whose medium was metal, whose muse was tradition.

Origins Etched in Earth and Time

Long before kings etched their names in stone and temples soared into the skies, the people of the Dhokra Damar tribe molded their legacy through molten brass. From the ancient ruins of Mohenjo-daro emerged a graceful figure—the Dancing Girl—her stance frozen in time, yet pulsing with the soul of a lost-wax miracle. This was not mere ornamentation; it was the birth of an art form—Dhokra casting—a method as enduring as the spirit of its makers.

Generations passed, and the technique wandered across the soils of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Bengal , Andra Pradesh, Telengana and Jharkhand. Nomadic families carried their skill like sacred lore, adapting it to local deities, harvest rituals, and nature’s temperament. The wax thread, coiled like destiny, formed elephants for prosperity, Lakshmi for abundance, and Ganesh for new beginnings.

Life Amid Fire and Silence

Inside mud homes, flickering flames whispered secrets. Tribal artisans—men, women, and children—shared work that blurred the line between labor and art. They would wake before sunrise, collect clay laced with paddy dust, mix it with cow dung, and form the humble beginnings of sacred forms. Their tools were simple: bamboo sticks, iron chisels, jute threads. But their spirit—unbreakable. Work was communal, spiritual, seasonal. Rain interrupted casting. Heat demanded patience. The wax had to cool just right, the fire had to roar just enough. And amidst this fragility, the strength of tradition held firm. Dhokra wasn’t just a livelihood—it was a way to converse with gods, honor ancestors, and teach children the geometry of devotion.Ties to Indian Cultural Soul

Dhokra didn’t remain confined to village altars or tribal markets. Its motifs seeped into India’s broader cultural bloodstream. During Margashira in Odisha, locals bought brass Laxminarayan idols from tribal markets—not as consumers, but as worshippers acknowledging shared sacred lineage. Art met faith, commerce met ritual. Even as modernity tiptoed in with industrial tools and digital platforms, the soul of Dhokra stayed tribal. Institutional trainings came and went, but the finest pieces still emerged from homes where pidha blocks, situni rollers, and kalup kolhi sticks whispered ancestral techniques. Yet the challenges grew heavier. Material prices surged, demand shifted, and younger generations weighed passion against practicality. But amidst this struggle, the flicker of survival still glowed.Where Tradition Still Breathes

Walk into any tribal village and you might still hear the crackle of wood in a casting pit, the hum of a plunger pressed into wax. You’ll see not just brass—but bravery. You’ll witness an art form that has survived empires, economies, and time—refined by hardship, but never erased. And as a Dhokra elephant quietly takes shape in a clay shell—its curves echoing sacred design, its hollowness filled with cultural memory—you’ll understand: this isn’t just craft. It’s India’s living soul, cast in fire and held in metal.

Raw Material for Dhokra Metal Casting

- Working board-maham pidha (working wood board),

- Modeling stick (kelub kathi),

- Beeswax-(Maham) is purchased from the village, where it was collected by the tribal people.

- Resin (jhuna),

- Grinding slab (the clay paste is groung with this stone) and hand stone (silo putta) iron blade, (Arisi patia) the wax press (Janta),

- clay (mati),

- lado ( fired clay) the fired shards of the clay forms are finely ground and mixed with the fresh clay to make it stronger against high temperature.

- cow dung (gobor),

- sickle (daa),

- hammer (Hatudi),

- Chisel (Chhini),

- weight machine (dandi),

- brass (pittal) when the brass objects like bowls, water vessels, measuring bowls worn out such items are sold to scrap metal dealer at half rate.

- Salt(luno),

- long picher (Bada Sanduasi),

Dhokra Model Preparation

The Dhokra technique begins with the creation of a clay mould (chhancha), shaped into traditional vessels, animal figures, and household objects. This clay core defines the inner hollow of the brass cast, capturing the intended design in simplified form.Core Types & Casting Techniques

- Open Core: Has openings for scraping out clay after firing.

- Closed Core (Chitamati): Made from sticky clay with sand and shredded jute (6:4:1). Remains inside the final cast to simulate heavier brass volume.

Clay Preparation

- Materials: Soil from paddy fields (rich in isless) and cow dung.

- Ratio: Mixed in 3:2 (soil to cow dung), pounded, sieved, soaked, and kneaded to a leather-like consistency.

Drying & Surface Prep

The sun-dried mould is smoothed by thumb and rubbed with green leaves. Leaf juice promotes wax adhesion for the next stage.

Cultural Note

Leaving clay in the final brass form can mimic solid casting, often fetching a higher market value due to perceived weight.

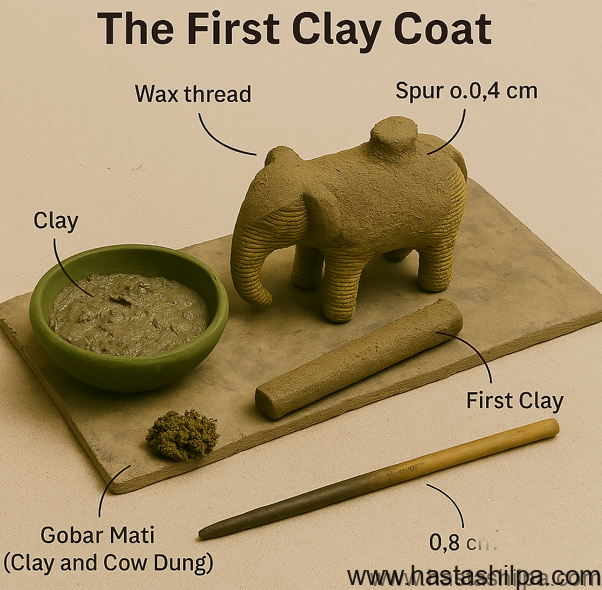

Wax Preparation for Dhokra Casting

Dhokra artisans purchase market wax—typically priced around ₹300/kg—as wild bee wax is hard to source. To enhance flexibility:

Mixing Process

- Resin (Jhuna) is blended with wax in a 1:10 ratio.

- The resin is first melted in a clay pot over fire.

- Then wax is added and boiled for 10 minutes, stirred constantly using a bamboo stick.

Filtering & Cooling

- The hot mixture is filtered through a cloth.

- It’s poured into a vessel containing water.

- Since wax is lighter than water, it congeals on the surface, forming usable layers for modelling.

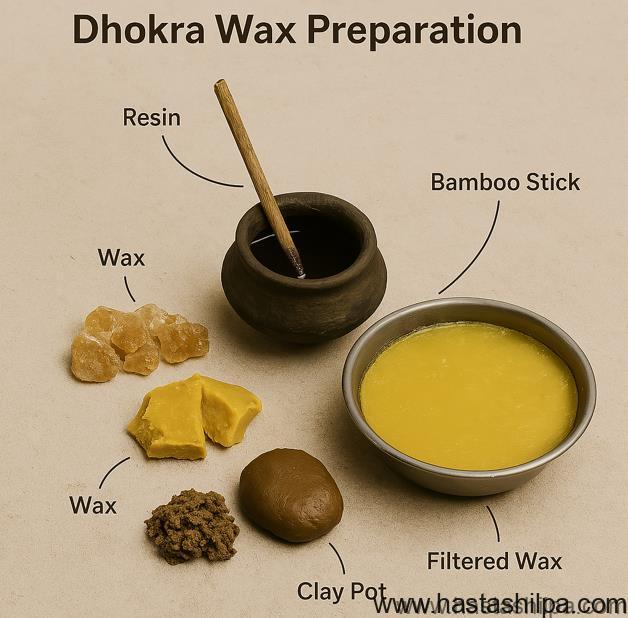

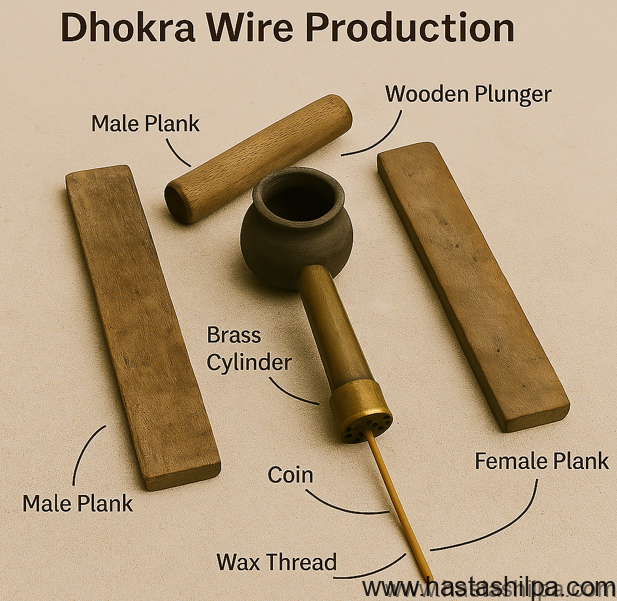

Wire Production in Dhokra Craft

This method transforms wax into fine threads used for intricate Dhokra detailing through a manually operated press.

Traditional Press Setup

Two wooden sticks (Jhanta Badi) form the press

Male plank (Andiapata) and female plank (Maipata).

- A brass or aluminum cylinder (Phungi)—engraved with symbolic motifs—is positioned on the female plank.

- Sieve coins (Chaki), with different-sized holes, are placed inside the cylinder base.

Wax Thread Formation

- Wax is kneaded until soft and ductile.

- The wooden plunger (Sulat) presses wax through the sieve with the help of full-body force, especially abdominal pressure

- As wax is pushed through the holes, uniform wax threads emerge, ready for application on Dhokra models.

Wax Thread Cooling & Decoration

After producing fine wax threads (0.5–1.5 mm in diameter), the artisan carefully wraps them around the clay mould’s surface, ensuring coils stay intact without flattening.

Decorative Detailing

- Each section—head, arm, leg, neck—is intricately adorned with wax designs.

- Where coils separate, a modeling stick (Kalup Kolhi) helps realign or blend the wax.

Supporting Tools

- Pidha: A marking block (42 x 17 x 8 cm) used for handling and guiding wax placement.

- Situni: A semi-rounded hand block for rolling wax into thread or flattening into sheets.

- Spur: Attached strategically—pressed or welded—to optimize metal flow during casting.

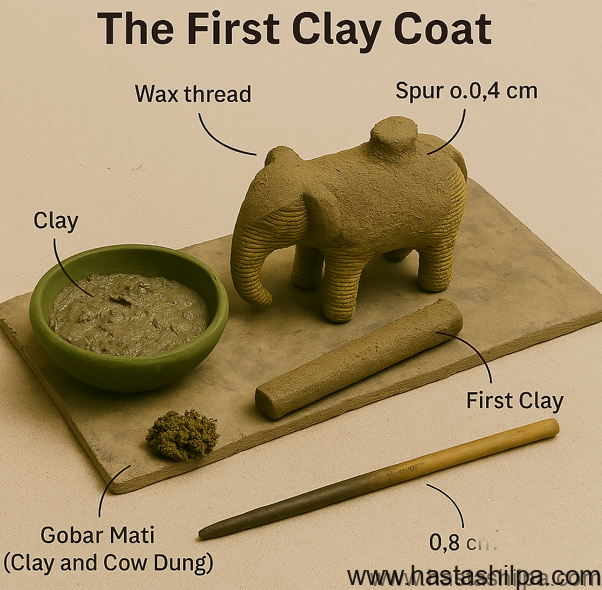

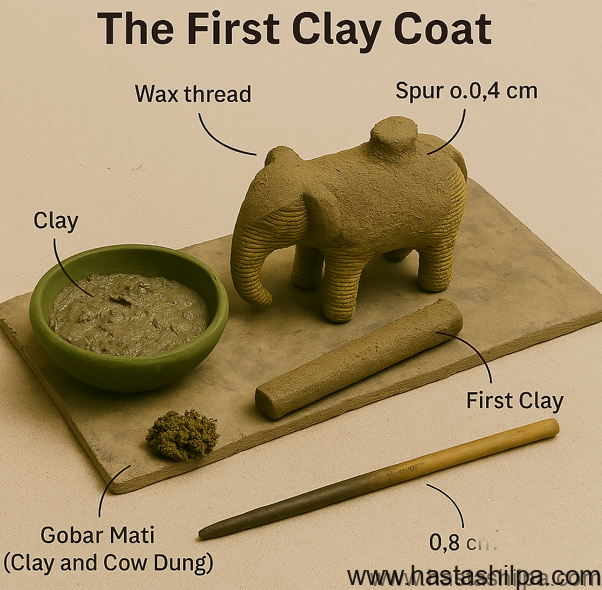

The First Clay Coat Application

Once the wax threads are fully wrapped, artisans apply a clay-and-cow dung mixture (Palkhania Gabarmati) to reinforce the form.

Material Composition

- Same blend as open-core paste, but with higher water content.

- Ratio: 3 parts paddy soil : 2 parts cow dung, ensuring pliability and surface detailing.

Layering Specifications

- Clay is applied to a thickness of 0.4 cm over the waxed surface.

- On the spur, it’s thicker—around 0.8 cm—to support molten metal flow.

- Critical to avoid inclusions or cracks, which may disrupt casting results.

Drying & Channel Setup

- One channel is provided for smaller objects, while multiple channels serve larger forms.

- The coated mould is then sun-dried, letting the outer shell firm up naturally.

Fixing the Closed Core in Dhokra Craft

To stabilize the clay core within the waxed mould, artisans ingeniously use tin triangles to lock it in place.

Triangle Preparation

- Tin triangles are shaped in a zigzag pattern using a hammer and chisel.

- A piece of iron is placed beneath the tin sheet to allow clean cuts.

Placement & Function

- These triangles are gently embedded through the clay and wax, spaced at 4 cm intervals around the form.

- Their job is to secure the clay core, preventing it from shifting when the wax melts and leaves a hollow cavity.

Applying the Second Clay Coat

This stage enhances the strength and structure of the mould before casting:

Clay Mixture & Preparation

- Blend: Soil, sand, and jute in 6:4:1 ratio.

- Soil is pounded, sieved, soaked, then mixed with jute and water into a firm clay mass.

Application Technique

- The second coat is applied to a thickness of 0.8 cm.

- A bowl of water is kept nearby to moisten the first layer if needed, ensuring strong adhesion between coats.

- All wax-covered lumps are fully enveloped.

Multi-Mould Arrangement

- Up to four wax models may be grouped depending on size and casting tradition.

- The fully coated moulds are left to dry overnight, solidifying the shell structure for the final casting.

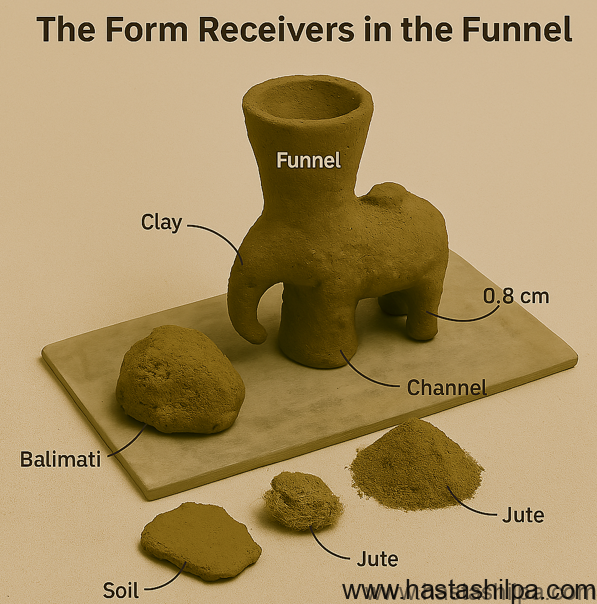

Form Receivers in the Funnel – Chunga Application

This stage ensures the controlled flow of molten brass into the waxed mould cavity via a clay channel.

Construction of Chunga (Clay Channel)

- Made from Balimati—a special lump of clay known for pliability and thermal resistance.

- Designed as a fixed conduit that directs molten metal from the funnel-like container to the wax interior.

Precise Placement

- The channel is positioned over the wax plug, leaving the plug visibly exposed beneath.

- Ensures accurate alignment for metal entry during casting.

Joint Reinforcement

- Outer joints are reinforced with thick clay for structural integrity.

- The entire setup is sun-dried to harden before firing, securing both the channel and plug in place.

Brass Metal & Its Cover for Dhokra Casting

In this phase, artisans prepare scrap brass and seal the mould’s channel to ensure successful metal flow during casting.Brass Sourcing & Preparation

- Market brass and worn-out objects like bowls, bells, and pots are acquired at roughly ₹500—half the cost of new brass.

- These are broken into scrap pieces, ready to feed the mould.

Channel Filling & Metal Enhancement

- The clay channel is packed based on the size of the wax models.

- A pinch of salt is added to the molten brass as a flux, improving metal flow and reducing impurities.

Cap Sealing with Clay Mixture

- A clay cap is placed over the metal-filled funnel.

- Cap and channel are joined using a clay, sand, and jute mixture (2:2:1).

- A thick roll of clay is layered across the middle channel to seal and reinforce it.

- Entire assembly is left to sun-dry, hardening it for the final firing.

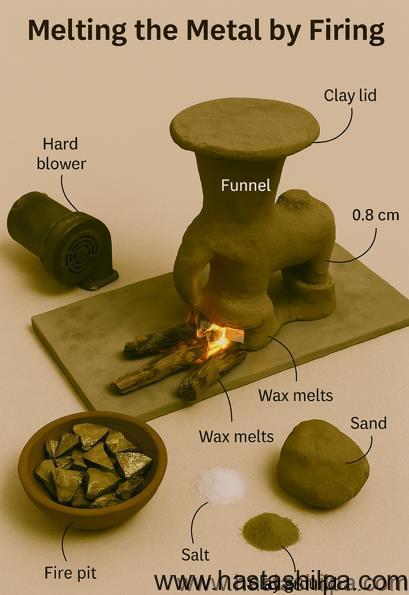

Melting the Metal by Firing – Dhokra Casting

This stage channels fire, force, and finesse to bring wax-moulded dreams into brass reality.Preparation & Firing

- Wood is arranged in a fire pit, surrounding two large or three small wax-clay moulds (metal side facing down).

- As flames catch, they turn yellow, indicating the wax is melting away, leaving a hollow cavity (lost-wax method).

- A blower machine intensifies the heat.

- A clay shield is placed atop the moulds to retain heat, accelerating the burning process.

Casting Phase

- After ~1.5 hours, smoke thins and flames turn green—a sign that casting can begin.

- With long pinchers, the glowing moulds are lifted from the fire and placed on clay ground.

- The crucible’s spout (pitcher) is tilted to pour molten brass into the hollow.

- The metal flows swiftly through internal channels due to the casting head’s pressure system.

Cooling & Finishing

- Moulds are laid upside down against a wall to cool.

- Once solidified, the clay shell is carefully broken, revealing the cast.

- Any rough edges are rubbed with sand to achieve a smooth, polished surface.

Conclusion: The Resilient Legacy of Dhokra Casting

Dhokra is more than an art—it’s a living tradition rooted in cultural reverence and generational mastery.

- Cultural Significance: Artisans create figures like Laxmi, Ganesh, Elephant, and Laxminarayan, deeply honored during Margashira in Odisha.

- Challenges of the Craft: Nearly 15–20% casting loss, unpredictable weather dependencies, and fluctuating material prices strain production.

- Struggles & Adaptation: Despite hard labor and minimal financial reward, many craftsmen continue this ancestral skill, though some seek alternate livelihoods.

- Traditional Continuity: Institutional support exists, yet artisans rely on informal training, age-old tools, and community wisdom to sustain their practice.

- Value Gap: Skilled craftsmanship often receives inadequate compensation, a mismatch that impacts long-term sustainability.